Ollie Pope’s confusing isn’t he… I mean it’s obvious to everyone that he’s no Test match number three, and then you look up his record and you see 1853 runs at 40.28 – and that’s after a tour of Pakistan in which his top score in five innings was 29 and he got a duck in a team total of 823.

He’s played 47 of his 92 Test innings at three, that’s 51 per cent, yet made six of his seven hundreds there, and scored almost twice as many runs as when he’s batted elsewhere. His record in the other 49 per cent of games reads – and Pope fans may want to hide behind the sofa – 1083 runs at 26.42.

So if Ollie Pope’s not a number three, then what is he?

Over the hundreds of years that the game has been played, certain things have resolved themselves, and one of those things is the batting order. At first it was a function of social status. Lords and Earls and patrons at the top; professionals, bowlers and northerners at the bottom. Ability had little to do with a good batting order. It was more like a delicately structured dinner table plan, sending out the necessary signals about breeding and money and empire.

That couldn’t hold of course and a batting order became about team function and form, about specialisation and productivity and then maximisation. Get your best players in for longest, give the best the best chance.

And each position assumed its own qualities. Those that inhabited it left behind some of their identity, and although all of those identities were individual, a hard-won consensus emerged. Where you batted was not just about your technique but your character and your personality, and a batting order evolved into a finely calibrated thing, as susceptible to interference as the cogs in a watch. When it worked it seemed obvious, even though it wasn’t really apparent to an outsider why batting at number four was a world away from coming in at number five.

Yet it was, and it is.

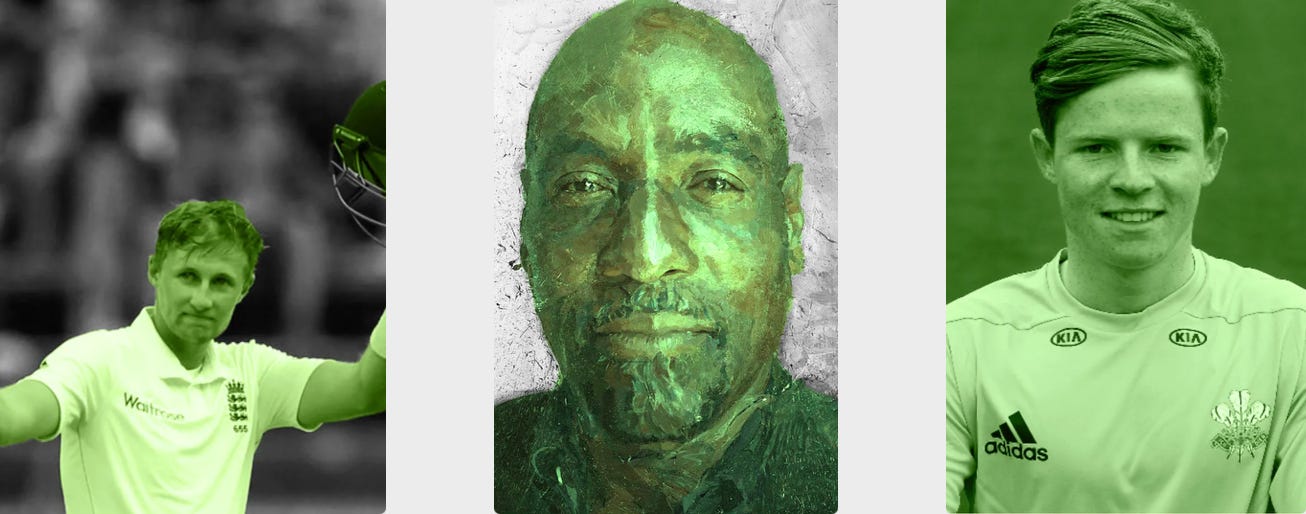

So, think of a number… This time the number three. The first player that comes to mind will probably depend on your age. I think of Viv Richards, then Ricky Ponting and Kumar Sangakkara. Greg Chappell from further back. Bradman played 56 of his 80 Test match innings at three. Number three, for me, has always meant the number of the big dog, the position of the best player in the team.

Richards and Ponting are the sine qua non. The core of their personalities run through the number three, to which they brought an uncompromising hardness alongside the brilliance of their shot-making. They each functioned as part of a team-within-a-team, coming to the crease behind a stellar opening partnership, in Richards’ case Greenidge and Haynes, in Ponting’s, Hayden and Langer. Together they were the top-order equivalent of a pack of rabid fast bowlers. With Viv or Ricky lurking, you sometimes didn’t want to take a wicket.

Four became more of a pure strokemaker’s position, the place where you’d see artists like Lara and Tendulkar and Mark Waugh, or a maverick like Kevin Pietersen. KP was a true number four in that his edgy desire to get started, fuelled by that last-minute tin of Red Bull, would have been exposed by coming in earlier. He needed that extra space. Brian Lara by contrast averaged more at three (3,749 runs at 60.46) than at four (7,535 runs at 51.25), so for him, it was more a matter of personal preference, the Big Dog sitting in the sunniest spot on the porch.

Tendulkar had the mighty rock that was Rahul Dravid one place above him, and Dravid perhaps best illustrates the other kind of number three, the kind who had the personality type of an opener, who was happiest coming in after an early mistake when bowlers and pitch were fresh and needed to be tamed. If you don’t have a Richards or a Ponting or a Sanga – and let’s face it, who does – then the answer is often to play a ‘third opener’ style batter. Jonathan Trott, for several years a key element of England’s best order of recent decades, was a fine example. Marnus Labuschagne is another. They’re not Big Dog types. They are more like shepherds, the protectors of their flock, there to avert harm and find the path.

***

Three of the new era’s Big Four, Joe Root, Virat Kohli and Steve Smith, have preferred number four. Perhaps that is to do with the relentlessness of the modern game, with Test after Test crammed together and the need to change quickly between formats with all of the technical and psychological adjustments it requires. There’s something about the severity of batting at three that not many players can get comfortable with. It’s unforgiving and exposing, and the desire to do it has to be naturally within you.

Kevin Pietersen had many Big Dog personality traits, but if you had to move him either one place up the batting order to number three, or one place down to number five, you would choose five, and I’m pretty sure he would too. Joe Root, the best England batter since KP, is the opposite. You would move him up one rather than down. Again, why? It’s as much about feel as it is about the numbers.

There is only one delivery between batting positions, yet collapses aside, number three probably has the most possibilities. You have to be able to go in during the first over of the game and bat like an opener, and walk out at 120-1 when absolutely everything, from the weather to the pitch to the state of the ball, the identity of the bowlers and the mood of the crowd, may be radically different from the first over of the day.

Where does all of this waffle leave England and Ollie Pope? The guy didn’t ask to bat three after all, Stokes and McCullum ‘identified’ him. What was he going to do? Say no? Give up cricket and run Clapham full-time?

Except, ironically, saying no would have been the kind of Alpha Dog trait that a proper number three had in their psyche. So the question becomes, who is the person that has said no to number three? It’s Joe Root, who by almost any measure is the best candidate for the post – but doesn’t want it.

A place in the batting order is about identity and self-image. Long ago, Steve Harmison said of the very young Ben Stokes – and I’m paraphrasing a bit here – ‘if you bat him at number eight, he’ll play like a number eight…’ There’s a deep truth to that. The numbers of the batting order have a power to them that has built up over hundreds of years of use. They mean something, and that meaning can exert itself in strange ways.

Unfortunately, Harmison’s observation doesn’t work if you flip it around. You don’t become a number three just by batting there and scoring a few runs from time to time – as England and Ollie Pope are finding out.

I think, perhaps, that Harmison might well be correct — ask Stokes to bat at no. 3, and he will bat like a no. 3!

What about Jacques Kallis. He wasn't even a proper batsman and then went on to bat at number three and then with Amla coming number 4. Such a solid player for the Proteas.