When I first started writing about cricket a few years ago, one of the best and most experienced writers was kind enough to go for a coffee with me. We sat in watery sunshine on a couple of spindly chairs outside a café in London, me trying to play it cool and not gush about how I’d read his stuff since I was a teenager and watched him play as a child before that. I knew enough to know that he wouldn’t particularly like that. He probably won’t particularly like this which is why I haven’t named him. Safe to say you don’t have to be Miss Marple to work it out.

Anyway, he was very kind, generous with both his time and the flat whites. The conversation inevitably rolled around to me somewhat dimly asking if he had any advice on how to make a living as a cricket writer. About as spurious a question as you can get. His response has stayed with me.

“Try not to follow the crowd. Do it your way.”

Then he said:

“Have you heard of Jimmy Breslin?”

***

In the days after JFK was assassinated in 1963, Jimmy Breslin, a 35 year old reporter and columnist for the New York Herald Tribune headed to Dallas to cover the immediate aftermath. America was reeling and the Texan city had magnetized the world’s media, with seemingly every person in the western hemisphere in possession of a camera, microphone or typewriter pitching up to report on the grim situation.

Jimmy Breslin was one of them. He would later recall having a remarkably clear state of mind amongst the mayhem and media circus. Jimmy Breslin had ice in his pen and a story to cover.

“I went to Dallas on November 22nd 1963 when Kennedy was shot” Breslin wrote later. “I thought that every minute of every hour I ever had worked had prepared me for writing about this. This is a marvellous emotion for you to have when a guy with a wife and two children gets shot. It is called news reporting.”

The day after JFK died reporters crammed into a poky, white-walled room at Parkland hospital for a press conference. Not content with receiving and regurgitating the same information as everybody else, Breslin pursued Dr Malcolm Perry for an interview – Perry was the surgeon that operated on JFK, the man who tried and ultimately failed to save the President’s life.

It is worth noting here that Breslin had also done stints as a sportswriter. Earlier that year (1963) he had published a book about the New York Mets’ disastrous first season called, ‘Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?’ – the title a direct quote from Casey Stengel, the Mets coach.

“You always went to the loser’s dressing room” Breslin said of his time as a sportswriter. ‘That’s where the story was’. In this case, the loser’s dressing room was Dr Malcolm Perry’s office.

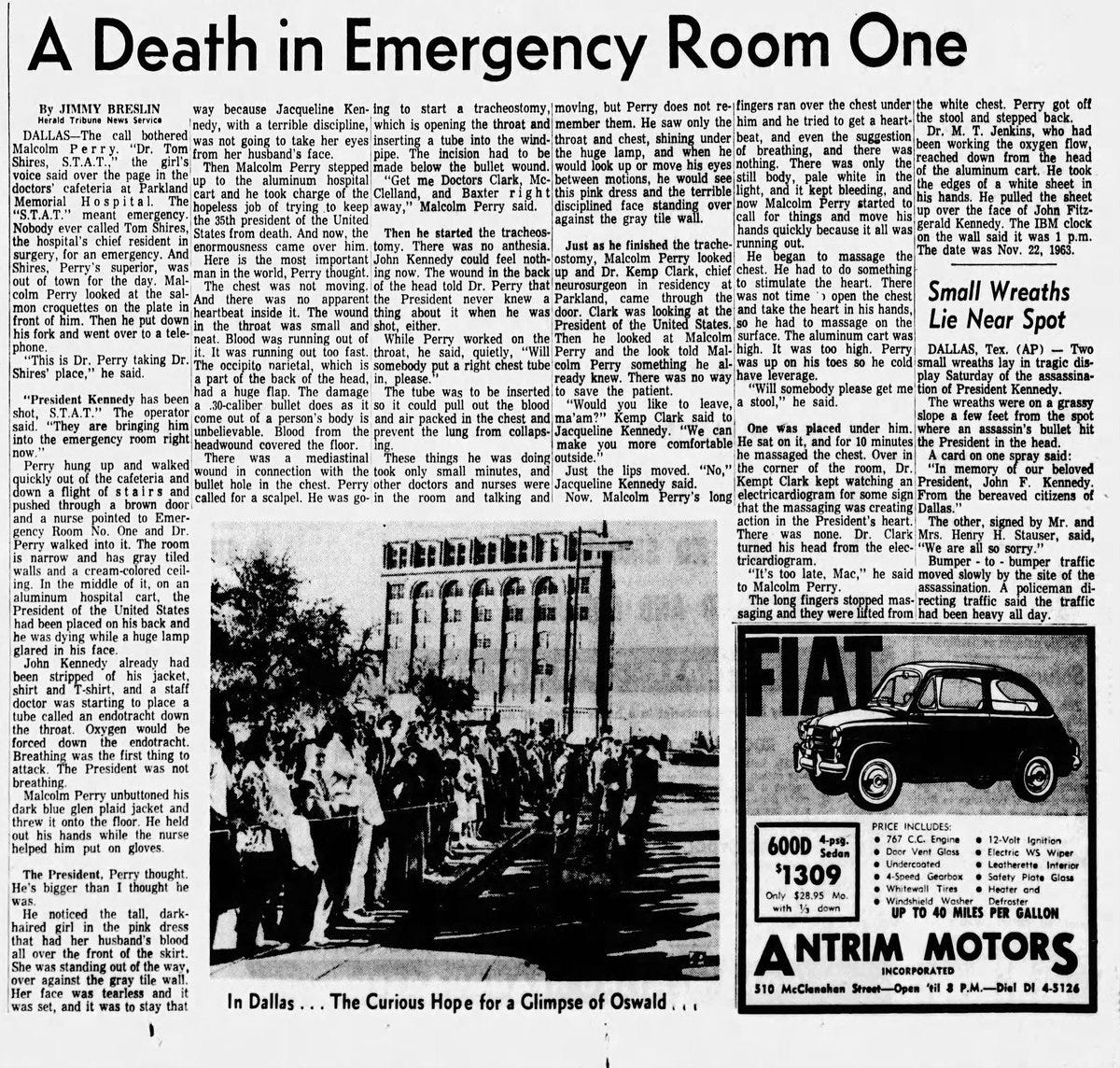

The ensuing column - ‘A Death in Emergency Room One’ was published in the New York Herald Tribune on November 24th, 1963.

“…a nurse pointed to Emergency Room One, and Dr. Perry walked into it. The room is narrow and has grey tiled walls and a cream-colored ceiling. In the middle of it, on an aluminium hospital cart, the president of the United States had been placed on his back and he was dying while a huge lamp glared in his face.”

There’s a fantastic HBO documentary about Breslin and Pete Hamill - fellow giant of American Journalism - called Deadline Artists. In it, family, colleagues, subjects and adversaries re-count stories of the two men. They all agree on one thing, ‘A Death In Emergency Room One’ changed the game. ‘It blew the doors off’ the way that news stories had been reported. Jimmy Breslin’s Runyonesque, literary and immediate style put the reader in the room, in the mind and behind the eyes of those witnessing, or indeed at the heart of history.

“John Kennedy had already been stripped of his jacket, shirt, and T-shirt, and a staff doctor was starting to place a tube called an endotracht down the throat. Oxygen would be forced down the endotracht. Breathing was the first thing to attack. The president was not breathing.

Malcolm Perry unbuttoned his dark blue glen-plaid jacket and threw it onto the floor. He held out his hands while the nurse helped him put on gloves.

The president, Perry thought. He’s bigger than I thought he was.”

A few days later, JFK’s funeral took place in Washington DC. Following his instinct once more Breslin wrote what would later go down as another classic column. Whilst everybody else was focussed on the funeral procession, the pageantry surrounding the White House and the blank grief shrouding Jackie Kennedy, Breslin headed to Arlington Cemetery and found Clifton Pollard, the man who had just dug the President’s grave.

“Clifton Pollard was pretty sure he was going to be working on Sunday, so when he woke up at 9 a.m., in his three-room apartment on Corcoran Street, he put on khaki overalls before going into the kitchen for breakfast. His wife, Hettie, made bacon and eggs for him. Pollard was in the middle of eating them when he received the phone call he had been expecting. It was from Mazo Kawalchik, who is the foreman of the gravediggers at Arlington National Cemetery, which is where Pollard works for a living. “Polly, could you please be here by 11 o’clock this morning?” Kawalchik asked. “I guess you know what it’s for.” Pollard did. He hung up the phone, finished breakfast, and left his apartment so he could spend Sunday digging a grave for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.”

The Deadline Artists documentary portrays Breslin in his pomp, cigar constantly lolling out of his mouth, smoke pluming around his stocky frame like dry ice as he clacks away at his type writer, resembling a silverback behind a toy piano. All the while barking down the phone in his machine gun Queens accent.

It also has footage of him as an elderly man looking back, with Pete Hamill, on a life in journalism. Like Breslin himself, the documentary doesn’t pull any punches – it details his relentless work shining a light on the plight on the poor and disadvantaged, of the civil rights struggle and in giving a voice to Aids sufferers and their loved ones, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1986. It also shows him to be epically thin skinned and self-aggrandising, Breslin fails to apologise for a racial slur at a junior colleague who dared criticise him and at times veers into boorishness and emotional coldness, even with his own family.

Breslin died in 2017 aged 88 with his legacy secured as a titan of American journalism. His columns and singular approach to covering stories are still taught in journalism courses across the globe.

Or so I’m told. Having never had any formal journalism training myself, the first time I heard of Breslin was from the esteemed writer sat opposite me at the café. This lack of training coupled with not being particularly well suited to some of its integral facets have led me to always feel uneasy associating with that word - journalist. Proper journalism is a skill, a trade, a craft. It probably teaches you how to sniff out a story, imbibe and present facts, use the correct words and proper sentence structure… deploy a semi colon; and, an oxford comma, correctly. It probably reinforces that tautology isn’t big or clever, great or brainy. How you should absolutely not dick about with your intro.

Of course, some of these are just grammar, the tools and rules of language, writerly chops. I’ve always preferred, if ever needed, to call myself a cricket writer, or sportswriter, or just writer. Whilst that may sound a bit highfalutin’ it doesn’t lay a claim to being in possession of skills that I’m well aware I don’t have. I could be a bad writer, a sloppy writer, a lazy writer or a dull writer but at least I’m not besmirching the art of journalism and those that studied it or honed the skills on the job. Or both.

What I took from the advice outside the café, or what I chose to take, was that there is a way to tell stories and look at the game from other, quirkier angles. To write the stuff you might like to read, to try, or at least attempt to try, to do something different. To poke your head into the loser’s dressing room. To seek out the gravedigger when everyone else is headed to the funeral.

There are of course an annoyingly talented few who can do it all. They can break news, write features and opinion pieces and weekly columns, match reports and colourful sidebars, get exclusive interviews and write them up with grace and flair. Broadcast and podcast, produce, edit, design, promote… In the face of all that, it’s hard not to sometimes feel a bit of a fraud. A one trick interloper.

With that and thoughts of Jimmy Breslin in mind, not to mention the need to get out and earn some fookin’ money as a freelancer, I found myself in a cricket ball factory in Walthamstow last week, the E1 postcode of this piece’s title. I’d visited the home of the Dukes ball the year before for a magazine piece investigating how a cricket ball is actually made, the interview I did with Dukes owner, Dilip Jajodia, then led to a shaggy dog mystery that is still ongoing*.

With the recent brouhaha about Kookaburra balls in the news, a discussion item on that morning’s BBC Today programme no less, I saw an opportunity to have a crack at doing some of the newsy stuff I’d always shied away from due to at times not having the stomach and at others, the inclination. I flung a text off to Dilip, would he like to get his viewpoint across as the head of Dukes balls? To respond to Rob Key’s comments that the Kookaburra was “fantastic” and that if he had his way the machine made ball would be a permanent fixture in county cricket.

“Yes. that’d be good” came the response. Too easy.

Or not. I found the whole thing hard and stressful. Juggling the demands of the interviewee, the sports desk at the newspaper, the nuance of the debate, the word count, the pressing print deadline. The newsiness of it all. I sweated over that 600 words more than almost anything else I’d ever written. I eventually filed and fell back into my chair. There was no endorphin filled high that you sometimes get when you press send on a piece, in its place was a blotchy red stress rash all over my chest and a weird twitch in my right arm.

‘I’m not cut out for this.’ I thought. I don’t think I should feel like I might be dying?

“Did you hear about Jim?”

“Yeh he carked it writing a news piece about cricket balls”

“Serves him right for pretending to be a journalist.”

The sports editor took pity on me, and took the piss, which made me feel better.

“Fair to say don’t go applying for a job as a crime reporter at The Sun”

I tried not to think about what Jimmy Breslin would’ve made of it all.

* Said shaggy dog tale will be posted in full on the site tomorrow, as a sort of companion piece to this one.

The Mystery of the Dukes Ball - can you help me find Walter? Breslin and Hamill would’ve cracked the case by now…