A nation of 5m to rule them all

The numbers game of New Zealand's success, plus a birthday tribute to one of the most extraordinary players of seasons gone by, Chris Tavare...

New Zealand have beaten India 3-0. In India. That is the India who had won eighteen series in a row at home, and lost four Tests out of 53. Well add another three to that list. For fans of the World Test Championship, it means (apparently, I haven’t personally worked this out) that India need to beat Australia 4-0 in Australia to reach a third consecutive final.

Yeah, right, good luck with that.

Although, who would not have thought exactly the same of New Zealand’s chances a couple of weeks ago? Stripped of their universally acknowledged best player in Kane Williamson, it’s probably worth a quick game of ‘who in the New Zealand side would get into India’s team?’

Would Tom Latham and Devon Conway take the places of Rohit Sharma and Yashasvi Jaiswal? No. Would Will Young, Daryl Mitchell or Rachin Ravindra get in a middle order that has Gill, Kohli and Sarfaraz? Rachin, potentially, maybe, but probably not. Could Glenn Phillips and Ish Sodhi oust Jadeja and Ashwin? No chance. And no-one in world cricket would pick Tom Blundell over Rishabh Pant. Just not happening.

And yet here we are, India 0-3 New Zealand. One seaming track and a couple of turners. There will be plenty of woe-is-me pieces deconstructing India’s performance, but what’s interesting is a question New Zealand throw up. They are in a real purple patch of their history, with the women taking the most recent T20 World Cup, a first global trophy for either men or women after some pretty heroic and heartbreaking near misses, and lest we forget, the men also won the inaugural World Test Championship.

The population of New Zealand is 5.2 million. Of the full member nations, it’s just above West Indies and about the same as Ireland. They’re less than a third of Zimbabwe’s 16m, way adrift of Sri Lanka’s 23m and Australia’s 25m, England and Wales’ 59m and South Africa’s 62m. Bangladesh’s 174m or Pakistan’s 252m – forget about it… As for the 1.4bn people they’ve just seen off in fine style by three matches to nil, well…

There is a point at the heart of this numbers game. How large – or actually how small – a population do you need to produce eleven cricketers that can compete at the very highest level of the game over a protracted period of time?

Naturally there are many factors in play, not least economic and cultural, educational and genetic. Any or all of those can discount huge numbers of any population, thus narrowing the field. I sometimes think about the vast populations of Russia and China, all of those millions… how many of them have the innate talent to be a Kohli or a Lara, a Warne or a Bradman, and yet they will never see a cricket ball? The numbers say that they must be out there, unknowing and unknown forever.

What we know is that five million people can produce enough players to beat a team from 1.4bn. How much smaller could it go? India could of course name three or four teams good enough to play Test cricket, but as the national side is limited to eleven at one time, that is somehow the great leveller.

***

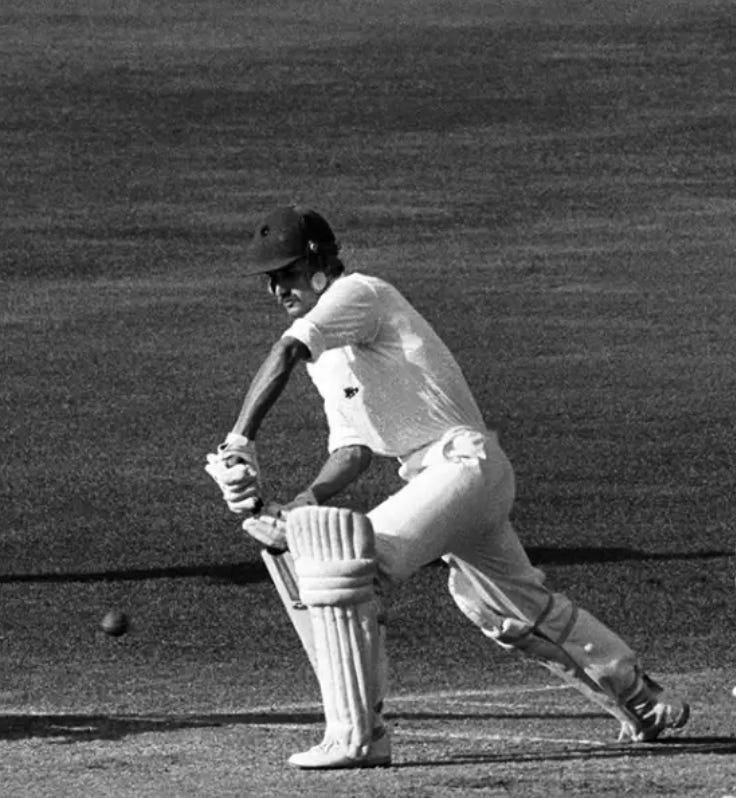

Chris Tavare, pictured in full flow above, turned 70 this week. The obvious joke would be that everyone else born at the same time has already reached a hundred, but I would never make the obvious joke. It did remind me of a post on my previous blog The Old Batsman, written in May 2011, the day after Tavare’s nephew William got his maiden first-class fifty. I thought I’d put it up here as a birthday tribute to the great man. Many happy returns.

There are some names that, as a young cricketer, you do not want. They are usually familial. The surnames of Botham and Richards were hard to climb out from under for Liam and Mali, because they stand not just for cricketers of note, but for something bigger: a way of playing the game.

Imagine then, that you are William Tavare, who made his highest first class score yesterday for Loughborough MCCU against Kent, a very respectable 53 out of 127 all out. Because as surely as Botham, Richards or Lara are names that come freighted with meaning, then so does Tavare. William is the nephew of perhaps the most extraordinary batsman to appear for England in the last 30 years, the motionless phenomenon that was CJ Tavare.

No-one who saw Chris Tavare bat will forget it in a hurry. If David Steele was the bank clerk who went to war, Tavare was the schoolteacher who took arms. Tall, angular and splayfooted, a thin moustache sketched on his top lip, he would walk to the crease like a stork approaching a watering hole full of crocs. Once there though, he began not to bat but to set, concrete drying under the sun. His principal movement was between the stumps and square leg, to where he would walk, gingerly, after every ball. If John Le Measurier had played Test cricket, he would have played it like Chris Tavare.

Tavare's feats remain the stuff of legend. His five and half hour fifty against Pakistan in 1982 was the second slowest half-century in the history of the game, and yet even that paled in comparison to the six and a half hour 35 against India in Madras the following winter. In a team that contained Botham, Gatting, Lamb and Gower, Tavare truly stood out. The mighty ballast which he provided against the Australians in '81 played a part in that famous win, albeit a part that never quite makes the highlights reels.

Like a lot of slow players, stories abounded that Tavare was a wolf in sheep's clothing, capable of pillaging county attacks on quiet Canterbury afternoons. If it happened, no-one remembers it now.

And so into a game that Tavare - now rather marvellously a biology teacher - would not recognise steps William. He got his fifty yesterday at a decent rate in the circumstances, but even if he turns out to be the next Chris Gayle, the Tavare name will plod after him, gently, and from a distance of course. Good luck, my friend.