Getting Hit

How do bowlers deal with hitting batsmen? Which approach works best against speed? When do you turn to Paul McKenna?

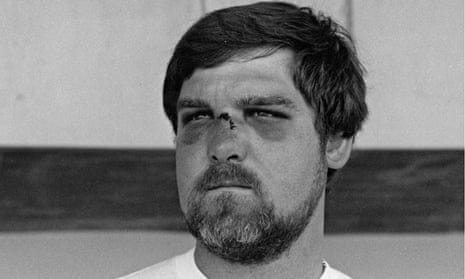

Farewell Peter Lever. A host of warm tributes followed the news late last week that the former Lancashire and England seamer had died at the age of 84. Michael Atherton wrote in The Times about how Lever had a “huge influence” on his own fledgling career when Lever was a coach at Lancashire in the mid-eighties. The warmth with which Atherton spoke of Lever sparked a memory of my own conversation I’d had with Lever five years ago, during the first 2020 lockdown.

The chat was arranged through Lever’s son Stuart and his wife Ros. Lever was nearly 80 then but still doing some coaching of a local side in Devon where he had relocated in retirement. I was doing a piece on what it is like to hit and be hit in cricket and so of course wanted to talk to him about Ewen Chatfield.

Re-playing the conversation on my dictaphone this weekend, I’m reminded that the move to the South-West had done nothing to diminish Lever’s Lancastrian accent, the conversation is peppered with those elongated vowels so reminiscent of my own Billinge born father. That linguistic similarity and Lever’s recent passing made re-listening particularly poignant.

Lever recalled the incident with Chatfield on the New Zealand tour of 1975 and his voice trembled as if it had happened yesterday.

“I don’t think I would have played cricket again if Ewen had died. I must admit.”

Lever told me he thought of the incident often but was so relieved it had a happy outcome. His sense of humour shone through most of all and he laughed uproariously recounting the story of fellow Lancastrian teammate Barry Wood’s “longest bloody duck in history” on the same tour.

Wood was called up as a last minute batting replacement and flew “around the world about twice” to get from West Indies - where he was doing some coaching during the English winter - to Auckland in time for the first Test. Lever recalled, through waves of laughter, about how Wood basically landed in his whites after two days of solid travel and more or less headed straight out to the middle to bat in a Test match. Inevitably, Wood was out to his very first ball, Richard Hadlee could smell the jet lag on him and made no mistake picking up a cheap Test scalp. A lot of air miles had culminated in a golden duck.

“All the other lads ran out of the changing room and left me on me own with Barry coming back in an almighty rage. I sat stock still as he entered and looked as if he was about to start trashing the place…” Lever went on to say that he caught Wood’s eye when the latter had his bat raised above his head like a Tudor executioner about to land the fatal blow. “There was a split second and then we both just burst out laughing, we were on our knees in fits of giggles! During a Test match. It was ridiculous!”

The thought of Peter Lever collapsed on his knees with uncontrollable mirth is in stark contrast to the famous image of him later in the same Test, buckled on the Auckland turf in the moments after hitting Chatfield with Derek Underwood crouched alongside, consoling.

“It's time that we began, to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again.”

The two opposing vignettes of Lever from that Auckland Test match made me think of that Leonard Cohen line. Lever went on to tell a lovely anecdote about the next time he encountered Chatfield a couple of years later, it was the perfect ending for the piece I eventually wrote. I’ve posted it in full below and am thankful we shared that conversation.

So long, Peter Lever.

***

It will take you longer than 0.4 seconds to read this sentence.

It will take your brain longer still to make sense of it. The fastest bowlers propel the ball at speeds in excess of 90mph. At the point of release, they are just shy of 19 metres away from their intended target. That’s if the intended target is the wooden stumps. A big if. The flesh and bone batsman, defending their stumps, body and pride (not necessarily in that order), is positioned around 17.5 metres away on the line of the popping crease. Some choose to take guard here; others retreat back towards their stumps in an attempt give themselves more time.

Because time is in short supply. Studies have shown that it takes a batsman 0.3 seconds to “react” − to process the line of the ball, make a judgment on its likely course and decide which stroke to play. It takes another 0.3 seconds for the limbs to receive the information from the brain and perform the shot. That’s 0.6 seconds in total – longer than 0.4 seconds, so something has to give. “Speed defeats reactions,” says former England fast bowler John Snow in Letting Rip, Simon Wilde’s thrilling exploration of fast bowling.

“Watch the ball” the old mantra goes. But when the ball is travelling too fast for the human brain to comprehend, there is a split second or so of guesswork, when the ball can be watched no more. That split second is crucial. It is the difference between staying in, scoring runs, getting out or getting hit.

Getting hit is part of the game. Batsman “hit” bowlers, but they strike the ball to do so, only wounding their pride. Bowlers hit batsmen with the ball. Some get hit worse than others. Some get up and live to tell the tale. Tragically, very occasionally, some don’t.

The death of Phillip Hughes in 2014 from a bouncer bowled in an Australian State match cast a long and unshakeable shadow over cricket. The game has changed since his death – the way we think, feel and talk about fear and danger is more perceptive, more open. The cricket world, united in grief, in turn threw its arms around Sean Abbott, the fateful bowler, to let him know that there was no blame attached to him, he was just doing his job. That Abbott is still playing the game and bowling fast at the highest level is testament to him and to Hughes’ memory.

“Playing fast bowling, you cannot fear pain,” says Robin Smith, who was renowned as one of the bravest and most skilful players of extreme pace bowling. “You know pain is a given. You know you are going to get hurt. Going to get hit.” The former England and Hampshire batsman enjoyed the thrill of testing his mettle and technique against the fastest. In his searing autobiography, The Judge, he even mentions deliberately letting the ball hit him: “I enjoyed a little sharpener on the inside of the thigh to wake me up.” That mentality would seem extreme to most readers, but this embracing of pain, the expectance and even acceptance of it, set him apart.

Not all batsmen felt this way. Steve James, the former England and Glamorgan opener, acknowledged as much in an article for the Telegraph. “Deep breath. Admission time. I was scared of fast bowling. Or to be more precise, I was scared of being hurt by fast bowling. I spent night after night worrying about it before matches... I am pretty sure many other batsmen had similar feelings, but I am not sure how many would ever want to admit it.”

No one likes fast bowling, goes the old adage, it’s just that some cope with it better than others. But Smith did more than just cope. He relished it. Thrived on it even. How did he do it? “You draw an imaginary line down the pitch, somewhere near the middle, and whenever the ball hits that line, you hit the fucking deck.”

“Everyone has a plan until they are hit in the face,” proclaimed Mike Tyson. It’s a line that could just as easily apply to batting. David Lloyd, who faced Thomson and Lillee at the peak of their powers during the 1974-75 Ashes, describes the “great thrill of playing against extremely quick bowling” and says: “It never enters your head that you are going to get properly hurt.” Then he got hit in the face. “Bob Cottam hit me and it shook me up. For a while after that I was very apprehensive. I don’t think I was the same player when I came back from that.”

Smith also eventually got seriously hurt, a brute of a delivery from West Indian fast bowler Ian Bishop breaking his jawbone and fracturing his left eye socket during a Test at Old Trafford in 1995. It affected him. “For the very first time I had a concern about being hit,” he says. “I was tentative in the nets and knew I had to do something about it or it was career over.”

He was put in touch with a young hypnotist by the name of Paul McKenna. “I had a few sessions with Paul, he put me under and – this might make me sound like a bloody fruitcake – but it made a huge difference. Afterwards I had a training session with Geoffrey Boycott and he had Paul Jarvis bombard me from 17 yards and I felt absolutely fine.”

England’s next series was against newly reinstated South Africa. The first ball Smith faced after being hit by Bishop was from Shaun Pollock. “He hit me straight on the helmet, the ball went down to third-man, and as I ran past him he said: ‘There’s plenty fucking more where that came from.’ But I was back to where I was before, I was fine. I can’t explain it. The hypnotism certainly worked for me.”

So what about the impact on the bowlers? “I never set out to hit or hurt anyone,” says Ian Bishop. “I would use the short ball to intimidate, or hope that the batsman gloves it to short-leg or that the follow-up delivery catches him on the back foot. The first time I hit someone I was a teenager playing a club match in Guyana and it really threw me off. It was shattering to see an opposition batsman bleeding. The senior guys huddled around me to protect me and I’m thankful that they said:, ‘Listen, this is part of the game at the highest level, you are just doing your job.’”

The sense that causing damage to batsmen is a by-product of the business they are in, rather than the intention, is shared by bowlers as feared as Dennis Lillee, Mitchell Johnson and Steve Harmison. All have written that they didn’t like hitting batsmen, but that there is inevitably an element of violence to their vocation. Harmison struck Langer, Hayden and most memorably Ponting on the first morning of the 2005 Ashes. “Fast bowling can get into your mind,” says the former England quick. “We were in their minds before they’d even gone out to face a ball.”

Harmison, like Bishop, speaks of having to get accustomed to hitting batsmen. “I hit Matt Cassar at the start of my career. That affected me, he was hurt. It stayed with me, that one, but I was a lot younger. There’s no point bowling a ball at someone’s head then feeling sorry and devastated if it actually hits them. It’s a job and you’ve got to get on with it.”

But what if those hits stack up and simply become too much to bear? Len Pascoe, a school mate of Jeff Thomson’s, was as fearsome as they come. The two played together for Bankstown Cricket Club in Sydney where local folklore has it that the nearby hospital had an accident and emergency wing named after them. Pascoe seemingly hit batsmen with relish, yet in his 11th Test match for Australia, he struck India’s Sandeep Patil a sickening blow in the face and was so shaken up that he lost the ferocity upon which he had built his reputation and ended up playing just three more Tests.

“After Patil, they all built up ... it did shake me up quite a lot,” he later told Cricinfo. “It was an accumulation of all the other blows. I spoke to Ian Chappell and said: ‘I want to retire.’ I was 32. I said the game’s not worth dying over. I was worried about what I was becoming. It wasn’t me. I don’t know whether I grew up or the bravado of the fast bowler was stripped.”

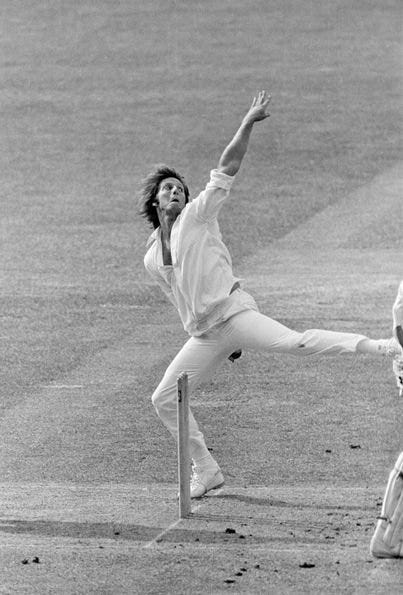

Peter Lever, the Lancashire and England seamer, was in the same beleaguered England team as David Lloyd during the 1974-75 Ashes. A grim irony befell him when, after surviving the onslaught dished up by Lillee and Thomson, he hit Ewen Chatfield on the New Zealand leg of the same trip. The Kiwi tailender collapsed and swallowed his tongue and needed chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation at the crease. Photos of the incident show a distraught Lever, bent double, visibly buckling at the unfolding trauma.

Lever, who is still coaching a local youth side near his home in Devon at the age of 80, confesses over the phone that he still thinks about Chatfield and the harrowing moments, hours and days that unfolded after he bowled that ball. “I don’t think I would have played cricket again if Ewen had died. I must admit.”

By the time New Zealand toured England in 1978, Lever had retired. But when he went to Old Trafford with his son, Stuart, a couple of New Zealand players frogmarched him up to their dressing room. “As soon as I went in they yelled, ‘Oi Chatfield, look who’s here!’ And Ewen turned around, saw me and ducked! Everyone started laughing. That helped me move on from it.”

What is clear is how vital the comfort and support of teammates and opponents are, as well as the reassurance and acceptance that hitting a batsman is part of the fabric of fast bowling and the game in general. Cricket would not be the same without the intimidation and risk that express pace brings. For all the bluster and bruises, pace affords pain and joy to bowlers and batsmen alike. And, if we have learned one thing when it comes to fast bowling, it’s that you simply can’t take your eyes off it.

*The piece originally appeared in Wisden Cricket Monthly and a version later appeared in The Guardian.