Graeme Hick and unmet promise

England's young blades bring to mind a Test played long ago, and the sadness that they may encounter along the road.

Jacob Bethell and Jordan Cox, 21 and 24 years old and both uncapped, go to New Zealand this month with Cox pretty much nailed on for all three Test matches as Jamie Smith’s understudy and Bethell a dodgy prawn or popped calf away from joining him.

The England team landscape is a place of change right now. Bethell and Cox are already in West Indies as a part of the white ball rebuild, a more urgent job than the Test side although there is a feeling that the five-day results are sort of on the slide too, the team resolutely mid-table in the World Test Championships and on a streak of three defeats in four games, their all-out approach questioned for the first time, the captain injured then cranky.

It’s a bit of a timeslip from here back to the dull cold of 6 June 1991, when Ben Stokes was two days old and England were about to play West Indies at Headingley in a Test that also had the feel of generational change. Both teams had captains pushing 40 for a start, England in Graham Gooch and the Windies in Viv Richards. King Viv had already announced that the final Test of the series at the Oval would bring down the curtain on his epic career, while Goochie was in late, full bloom. The previous summer he’d hit India for 333 and 123 at Lord’s, and in this game he would play perhaps his greatest innings, carrying his bat for 154 and setting up England’s first win over West Indies in a home Test since 1969.

The West Indies squad featured a young Brian Lara, at the back of the queue for a batting spot in the Test team and whose main duty was to chauffeur his captain around between games. England would field three debutants of their own at Headingley, the quick bowler Steve Watkin, who found out he was playing shortly before the toss when Chris Lewis came down with a migraine, and two batters of shimmering promise, 21 year old Mark Ramprakash and the 25 year old Graeme Hick.

It was hard to know which of the pair carried the greater hopes. Ramprakash had debuted for Middlesex at 17 and a year later been man of the match in a Lord’s final. His maiden first-class hundred had come at Headingley, and many years later, when all of this was done, his one hundredth would come there, too.

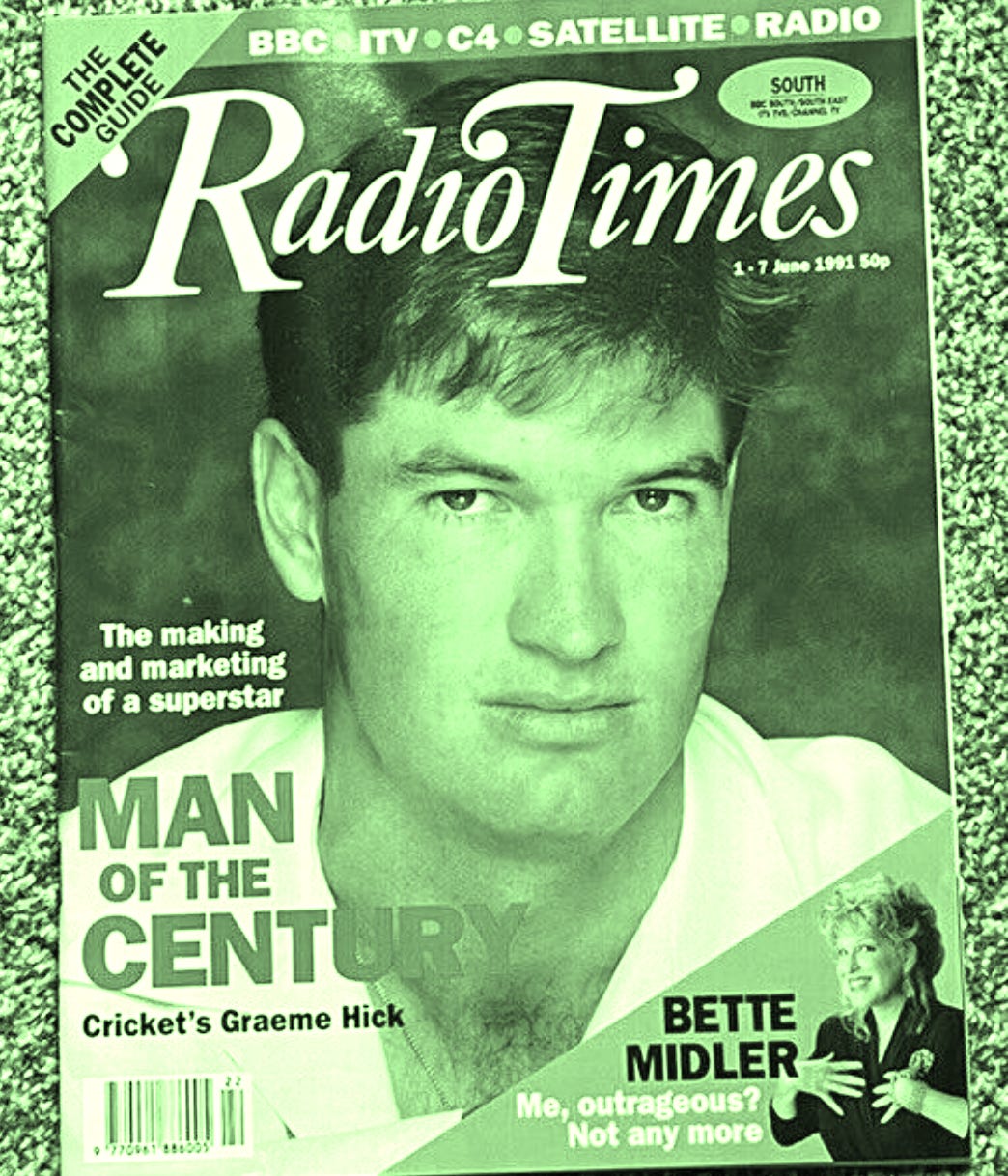

Hick, five years older, had also been a teen prodigy back in Zimbabwe, the land of his birth. At thirteen, he averaged 175 for his school team, and he was chosen for Zimbabwe’s 1983 World Cup squad one month after his 17th birthday. He came to England a year later on a scholarship, and for Worcestershire Seconds made scores of 195, 170 and 186. He looked so good he was picked in the first team for the final Championship game of 1984, and batting at number nine scored an unbeaten 82 in Worcester’s second innings.

In 1985, he made the first of what would become 136 first-class hundreds when he got 230 for the touring Zimbabweans against Oxford University. The following winter, he made 309 for Zimbabwe against Ireland. By the time he turned 20 in 1986, he’d been capped by Worcester, and two years after that, passed one of the great landmarks of batting in England: a thousand runs before the end of May. He did it by scoring 405 against Somerset and then 172 against the touring West Indians.

By now, Hick was wintering in New Zealand, battering ten hundreds in two seasons for Northern Districts, and scoring a record 173 between tea and the close in a game against Auckland. It was an innings so dominant it led to the disgruntled Auckland coach John Bracewell calling him “a flat-track bully.” No-one took any notice of that.

Zimbabwe did not hold Test status, and so Hick was free to qualify by residency for a full member nation and take his apparently rightful place at the pinnacle of the game. England’s qualification period was seven years, and Hick could start counting from his first Worcester appearance in 1984. New Zealand jumped in with a cheeky counter-offer of a four year qualification, but Hick chose England, and by the summer of 1991, as he passed the seven year mark, he was the surest thing around.

He didn’t have to wait long. At Headingley, another highly-rated youngster named Mike Atherton, who had already made three centuries in his first 13 Tests, was bowled by Patrick Patterson after twenty minutes of play. To the manor born, Hick strode out and scored six before he was caught behind from the bowling of Courtney Walsh. As he walked off, Mark Ramprakash walked out.

Graeme Hick scored six in the second innings too, and then made scores of 0, 43, 0, 19 and 1 and was dropped for the final Test of the series. In a strange circularity of numbers and fate, Mark Ramprakash also made identical scores in both innings at Headingley, 27 and 27, a score that would become his final Test average.

Hick’s was a smidge higher at 31, and he got six Test hundreds to Ramprakash’s two, and yet they would as a pair become emblematic of England’s cricket during the 1990s, endlessly dropped and recalled, first traduced and then built back up, with many thousands of words spent on the reasons why. Was Hick too diffident? Ramprakash too highly strung? Was it even their fault at all? How would we ever know.

They had to find fulfilment in different arenas. Hick, dogged by John Bracewell’s taunt, scored more runs in professional cricket than anyone who ever played except for his captain that day at Headingley, Graham Gooch. Ramprakash had the summers of 2006 and 2007 when he somehow, unfathomably, averaged more than 100 across both seasons. They were the last two players to cross the great boundary of 100 first-class centuries, and it’s hard to imagine that anyone else will follow them.

There’s some consolation to that, and to all of their other records. Cricket is a game of hope and promise, but most of all and beyond everything else, it is a game of failure. Most players fail most of the time. Hick and Ramprakash were emblems of that, and of a decade of English cricket that was one of the hardest to succeed in, for reasons as far apart as the environment it created and the brilliance of the opponents that they faced.

Unmet promise has a sadness to it that won’t be shaken off, because youth, once gone, can never return. Mark Ramprakash and Graeme Hick have had to come to terms with that eternal truth, and some of England’s dazzling new crop will inevitably have to do the same.

I also wondered in the 90s and early 2000s that why were they not consistent witha good English line up to challenge other teams along with Butcher, Athers, Nasser, Thorpey and Gaffer.

England not beating West Indies in a home test between 1969 and 1991… Seems an incredible stat now despite knowledge and memory of Clive and Viv’s teams, but really, that far back?