Joe Root and the super-scorers

Thirty-one more runs at Old Trafford puts him on the podium of greatness. But what does it all mean?

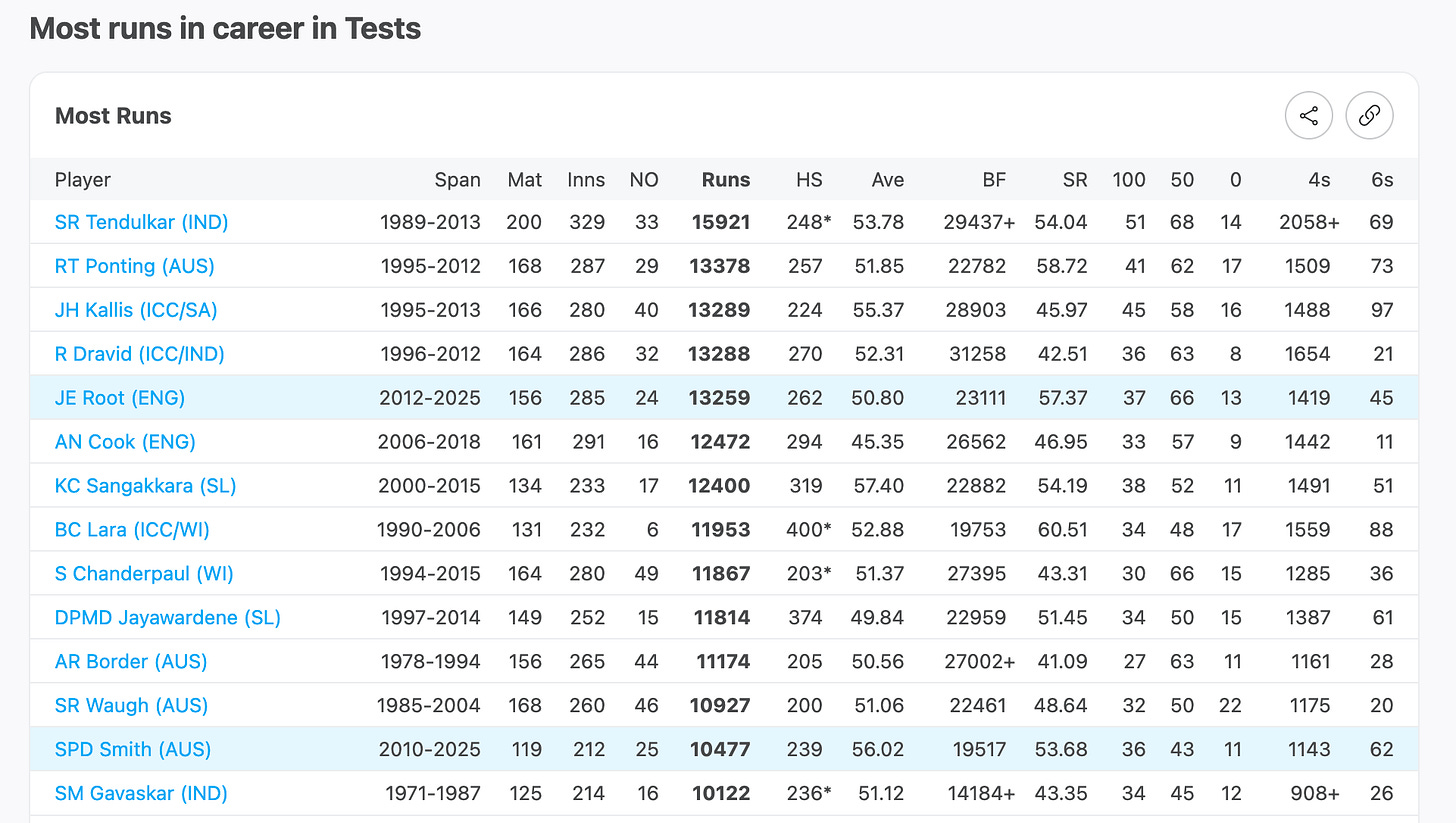

Someday very soon, probably at Old Trafford, it will happen. Maybe it will be the glide off his legs from a delivery he has judged just a fraction too straight, or perhaps the ball will meet a bat face slipped open by knowing hands and hurry, as it so often has, through that gap between backward point and gully to the fence. However it comes, Joe Root will score the last of the 31 runs he needs to go past Rahul Dravid and Jacques Kallis – themselves separated in history by a single run – and into third place on the list of all-time highest scorers in Test match cricket.

Given the exalted plane that his batting has reached since he unyoked from the deadweight of captaincy, it’s no stretch to imagine him making the 119 he needs to surpass Ricky Ponting and move into second place, too. Over his 156 matches he has averaged around 85 runs per Test, so the Punter is not far away. Only Sachin, a glittering summit stretching far, far above will remain, an Everest that still may never be scaled - because if Joe Root doesn’t do it, then it’s hard to think who will.

Tendulkar is 2,543 runs past anyone else so at current rates, Root will need another 30 or so Tests to get there, and no-one can guarantee him those. It’s two to three years of continuous cricket even without injury or some unforeseeable and catastrophic dip in form or desire. Should he hold out, Root will be close to 40 by the time it happens, and life comes at you fast.

Geoffrey Boycott was the last England batter to hold the progressive record. He took it from Garry Sobers in 1983 but kept the mark fleetingly before Sunil Gavaskar went past him a year and 324 days later. Sunny would reign for almost a decade before Allan Border took the baton and stayed ahead for 12 years. Brian Lara beat Border, but he got less than three before Sachin took his place. That was in October 2008, so Sachin has had almost 17 years and counting. Even he, though, must yield to Wally Hammond, who got 33 years at the top before Colin Cowdrey caught up.

Boycott made 8,114 runs, a total that Joe Root went past in his 99th Test match, against Sri Lanka in Galle in January 2021. Over his next seven Tests he pretty much knocked off the elite of English batting, overhauling Pietersen, Gower, Stewart and then Gooch by August of that year. Only Alastair Cook lay ahead, and Joe waved his old pal farewell during his epic 262 in Multan last October.

Root is one of 33 cricketers to have gone past Boycott’s total. That marks not just successive generations of great batters, but the acceleration of life in the post-internet age. Of those 33, only four have played fewer Tests than Boycott’s 108, and none less than 104. All of the top ten runscorers played well into this century – Lara being the first of them to retire in 2006. Even by this measure Root’s career has been one of the most concentrated ever: his 156 matches have come in 13 years. In comparison, Rahul Dravid’s 164 took 16 years, Ponting’s 168 were played over 17, Kallis’ 166 lasted 18. Tendulkar’s mighty 200 caps occupied almost exactly 24 years – Joe Root would still be playing in 2036 should he match Sachin’s span.

To have played so consistently at that intensity is maybe his greatest achievement. And to have made it so frictionless is the true mark of Root’s greatness. His batting is a sense-memory of craftsmanship, conditions assessed, a method calculated and then adjusted with infinite subtlety in response to urges that slip upwards from his subconscious mind, which has been deeply schooled by all of that experience. Small shifts in guard and position, a little further forwards or back into the crease, a meeting of speed and angle, a flow of mind and body delivered in smooth miliseconds. The remarkable thing is its unremarkability, how rarely he is bothered by anything. The runs roll by like a river, a kind of permanent transience when nothing is ever quite the same and yet always looks it.

I once got to ask Mark Ramprakash about the sublime period of runscoring he had when he averaged more than a hundred in first-class cricket for two whole seasons. How had he done that?

“I suppose the feeling was that I had created a momentum where things were going my way,” he said. “A number of things came together, where you’ve given yourself every chance to be successful. Physically I was in good shape. I knew the grounds well. I had experience. I did my homework on the other players. I felt mentally relaxed. I’d often chat to the umpire at the non-striker’s end about football or anything else. I was much better at switching down and switching up. All of these things came together. I had a great balance between being really tight and committed to my defensive game, but then when the opportunity arose, I attacked with one hundred per cent commitment. As soon as the bowler was off line or length…”

As a public figure and a former captain Root is somewhat opaque, too media savvy to say anything interesting, let alone revealing, about the state he is in and how he intends to go on. Why set yourself up for that? Temperamentally, he’s far more like Tendulkar than Ponting or Lara – or Mark Ramprakash for that matter, a calm and benevolent deity of the willow. Does he sense the scale of what he is about to achieve? What does it mean to him? Does it mean anything at all? Because we know that the stats are simply the outcome, and batting is about process, about the single moment. Does Joe Root enjoy his life of hotels and travel and practice just to do this thing, to have this moment, or it it simply all he knows?

At these things we can only guess. From the outside, he stands 119 runs away from being the second-most prolific player to have picked up a bat, and yet because what he does is so unflashy, so machine-tooled and regularly produced, we have lost sight of its scale.

In a land of giants, he has become one.

Joe Root has a strong chance of climbing Mt.Tendulkar. The amount of test cricket England plays, and he plays for that matter, there is an opportunity for him to do so. Even with a slight dip in form, he can reach near that mark in this WTC cycle itself.

But at this point, only time can tell where he will finish. By the time he turns 35, he will have played 162 test matches and at the current rate will be somewhere around 13600-13700 runs. His form in the Ashes will be a factor as well. You never know that one day he, despite being fit, decides to go Alastair Cook's way and calls it a day. Or it happens like James Anderson.

Good point re the Ashes - how will he go? It's the last great unknown for him, really