On Hating Fielding

Boring, tiring and with an ever-present edge of terror, why wouldn't you?

I wrote this essay for my book Bat, Ball & Field, but thought it would make a half-decent bank holiday piece, given you might well have spent a large part of the weekend doing it. I did. And by it, I mean fielding, the one part of the game no-one can avoid…

The twenty-fifth and in all likelihood the last player to score one hundred first-class centuries walked from the arena for the final time on 4 July 2012, taking one of the great landmarks of batsmanship into history with him. Mark Ramprakash so loved the game that he carried on until he was 42 years old, but when someone asked him what he would miss the most about it all, he said, ‘well it won’t be the fielding…’

There are lots of things that the amateur cricketer finds hard to conceive about the pro game, mostly the speed and power of it, its unrelenting, day-on-day nature, the rigour and discipline needed to produce the finest of motor skills on demand again and again, but most of all, it’s the fielding. Amateur cricket is over and done in an afternoon, a day at most, and with luck only half of that time will be spent in the field. The pro is regularly out there all day, three sessions of at least two hours each, often in hostile conditions, sometimes while up against it and occasionally when the wheels are coming off. The field is a factory floor, governed by a slow-moving clock, a place of labour.

Most of cricket is about failure. By the numbers, batsmen fail to make their average score two out of every three times they bat. Bowlers have around a one in sixty chance of a wicket with their next delivery. Failure is quotidian, the usual outcome, and so it is accepted hundreds of times per day. But failure in the field is not, at least not in the professional game. The pro is expected to stop every ball, hold every catch. Assembling a decent slip cordon can be as complex as developing a batting order. The relationship between wicketkeeper and first slip needs some of the wordless understanding of a good marriage; the speed and feel of a ball deflected to third slip, usually dropping more quickly than one edged finer, is wildly different to a ball off the face of the bat that flies to gully, and yet the fielders are separated by no more than a few yards. Pros drill these things endlessly. Like boxers, who for every round in the ring fight ten in sparring, they take thousands upon thousands of catches every season in practice. When they don’t, there’s often a downward spiral, and how a team fields is a glimpse of its inner life.

Dropped catches can be sliding doors moments. England won one of the most extraordinary Test matches of the modern era by two runs at Edgbaston in 2005, the finish, with Australia’s number eleven Mike Kasprowicz gloving a short ball from Steve Harmison to the keeper Geraint Jones just as defeat looked certain. It has been endlessly replayed, yet it almost didn’t happen. With Australia needing fifteen to win, Kasprowicz ramped a ball to in the air to third man, which Simon Jones dropped. It was a hard catch but one Jones said he’d taken ‘hundreds of times’ in practice and other games. ‘That,’ he said, ‘was the worst feeling I’ve ever had on a cricket field.’ To compound matters, he was fielding in front of a section of Australian fans, who’d been swearing at him all morning.

‘Cheers Jones,’ one shouted. ‘That was fucking useless…’

It seemed like a chance, the chance, to win the game. There is often one but rarely two. There were lots of reasons to drop it. The tension was by that point overwhelming: had England lost, Australia would have taken a two-nil lead in the series, which was more than likely insurmountable given their greatness. England hadn’t won the Ashes for eighteen years, so the weight of all of those was on that catch too. As Simon sprinted towards the ball, it dipped below the skyline, where it was easy to see, and against the stand opposite that was filled with people. He lost sight of it, and it didn’t reappear until it was right in front of him. And like all of the players, he was drained by the match and the occasion.

But this was the chance and he should have caught it. The moment was forgotten when England won, and the narrowness of their victory set the series on its immortal path. Simon Jones, though, barely remembered those final minutes.

For all of the advances in batting and bowling, nothing in the game has moved on like its fielding. Newsreel of Bradman is almost comical, fielders trotting after the ball once it passed them. No wonder he scored so many. The commentator Henry Blofeld knew Bradman well, and I once had the chance to ask him about what fielding then was really like. ‘It was better than it looks,’ he said. ‘Players didn’t dive, but they stopped the ball, they caught well. On the newsreels you only see the balls that go to the boundary, and so it seems odd. And Don was a master of placement, among many other things…’

But the culture has changed. In the World Cup final of 2019, with New Zealand needing two runs from the final ball of the super Over to win the match, and under almost unthinkable pressure, Jason Roy, England’s boundary rider, ran towards the ball, gathered cleanly, chose the right end to throw to. Seen live rather than on TV, that throw came in like a bullet, powered by fear and adrenaline. And Roy deliberately landed it a few yards short of the keeper Jos Buttler, who turned and broke the stumps with Martin Guptill short of his ground. Anything less than what Jason Roy did, the slightest discrepancy in his accuracy or power in the throw, and England’s four years of planning to win the World Cup would have meant nothing. Earlier in the Super Over, he had fumbled almost exactly the same ball. Amid the mayhem and ecstasy (for England at least), Roy’s throw was hardly talked about. It was simply expected, drilled over hundreds of hours for those few short seconds, that one perfect throw.

Grace said that, ‘the best place to put a duffer is mid on.’ I have spent many thousands of overs there. It feels like my front room now, an angle on the game I’m so familiar with it sometimes feels odd to be anywhere else. Fielding in the pro game may be futuristically brilliant, but in the stiffs, the Don would feel right at home. For most of the years I played, I hated fielding. It was simply the trade-off for the chance to bat. It was usually boring and tiring, but with an edge of terror, too, a fear and loathing of a mistake and how it will make you feel. The Captain’s gaze can burn you in those moments. You know what they’re thinking, and your mind starts to wander to the next selection meeting, what they will say…

A lot of amateur cricket concludes with twenty overs to be bowled in the last hour. It always, without exception, takes longer, the time dragging, the result, whichever way it is going, often inevitable. You’re just waiting…

The biggest change in the game since I’ve been playing is how hard the ball is hit. It’s absolutely smoked now, especially by younger players who have grown up on T20 and have no fear. they just want to smash it in the way they see it smashed on the TV, and they do. The first few weeks of the season, usually conducted in numbing April cold, can be nightmarish, your hands yet to toughen up, the ball slamming into chilled fingertips, trying to chuck it back while wearing three layers and praying no-one hits it in the air in your direction…

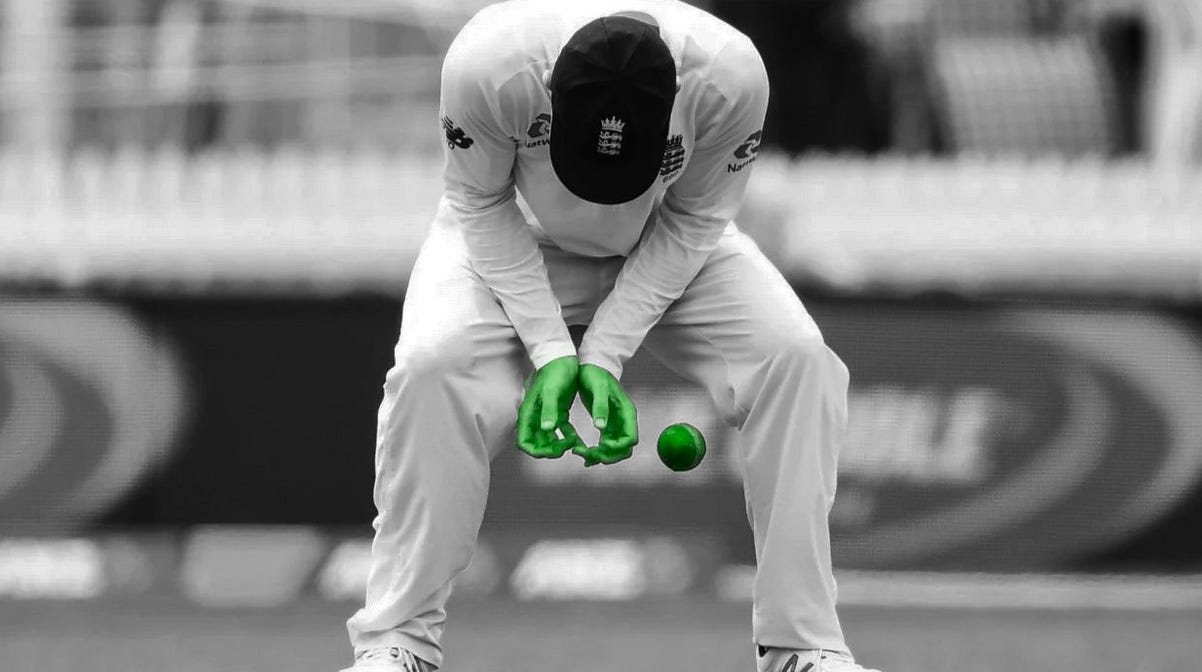

There’s no feeling in cricket quite like dropping a catch. It’s not like failure with the bat or the ball, which is more personal. It’s a failure that directly and immediately affects the bowler and the captain. It feels like a hollowing out of the spirit. It weakens you psychically, sometimes physically. Success and failure in batting counterbalance – the satisfaction of playing well is great enough to offset the disappointment of missing out (two in three, remember…). Unless it’s a brilliant one – unlikely in my case – the dominant emotion on holding a catch is simple relief. There’s no fair exchange with the emotions of dropping one.

And yet cricket turns another face towards you as you get older. I hated fielding and then, before I’d really noticed, the feeling had turned into something else – not love exactly (let’s not get carried away here) but an appreciation of all it offered. In his novel Netherland, Joseph O’Neill describes the rhythm of fielding, walking in as the bowler runs up, as ‘pulmonary’. It’s an in-out with every ball, six times an over, again and again, through matches, through seasons, through decades. I have spent way longer fielding than I ever have batting, and now, on sunlit late afternoons on perfect grounds, I sometimes look around at the people I’m playing with, friends I’ve known for years, and feel a bond forged in shared experience, in walking in and out together for all of those overs, knowing something now that I didn’t know back then, when I hated everything about it: nothing, not even fielding, lasts forever.

A quick, hopefully forgiveable plug. The Amazonian empire has a good deal on the paperback here. Or at your choice of bookstore. Jimbo will be back later in the week with some brand new stuff…

I love fielding! Of Course, it’s never for more than 40/45 overs, and as a bowler the time is broken up, but it’s where I feel most like I’m actually playing cricket rather than watching it. You’re never more alive than standing at slip to the new ball or at long on / off waiting for a skier later in the innings. Drops? It’s the one thing in the game we ALL do but when they stick there’s no better feeling. In 20-odd years’ time, when I’m finally finished I reckon it’ll be the catches and those moments in the field that’ll bring wistful tears to the old eyes.

(I should add I can’t run at ANY speed and have, in 45 years of playing, never been able to throw a ball overarm 😊)