Reputations: Ben and Ian

In the second of our series, the all-rounder that no-one could follow, and the all-rounder that did...

A few years ago I was at a dinner at Lord’s with some other writers and also – clanging name drop – Mike Atherton. I can pinpoint the date for one reason: Ben Stokes and Alex Hales had been involved in a fight outside a nightclub, unforgettably named Mbargo, after an ODI in Bristol, and film of the incident had just been made public, so it would have been the autumn of 2017.

Athers was characteristically brilliant that night. Although he was the man that people were there to see and hear, he insisted on acting as MC and intro-d the other writers who would take part. When he got to me he said something like, ‘the only thing wrong with him is his obsession with Mark Ramprakash…’ which obviously got a laugh and admittedly contained a kernel of truth – the ups and downs of the great Ramprakash were something I’d written about a fair bit, and rightly so in my opinion.

Mike had captained Ramprakash during many of Ramps’ tortured stints in and out of the England teams of the 90s. He’d even opened the batting with Graham Gooch at Headingley in 1991 in the game where Ramprakash and that other enigma Graeme Hick made their Test debuts, so he’d had a ringside seat at the circus. My no doubt overly-romantic view of the travails of our hero is not one that he entirely shared, and I got an insight into the sheer toughness of the professional dressing room, a glimpse at its unforgiving demands on everyone inside it.

One thing we did agree on was that the ECB had been right to announce that Ben Stokes would not go on the Ashes tour that winter. It seemed to be as likely that he would go to prison as to Australia. It was that subject, rather than Ramprakash, that really engaged everyone in the room, and opinion was split. Plenty of people thought that the ECB’s decision was needlessly destructive to player, team and country.

It appeared that Stokes was on the same path as the two all-rounders that stood as generational avatars for the England team and the English game, Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff. Stokes had not yet produced the deeds that would sit him alongside them, although he had the same lightning rod appeal to the public, a lionhearted spirit that brought about on-field miracles but that carried with it an excess energy that meant there could be no quiet life. Botham had his bar brawls and broken beds, Flintoff his pedalo and his binge-drinking (and never was he more loved than when he was staggering out of Downing Street cross-eyed with booze the day after the 2005 Ashes). Now Stokes had a punch-up of his own, and its inevitable downward course.

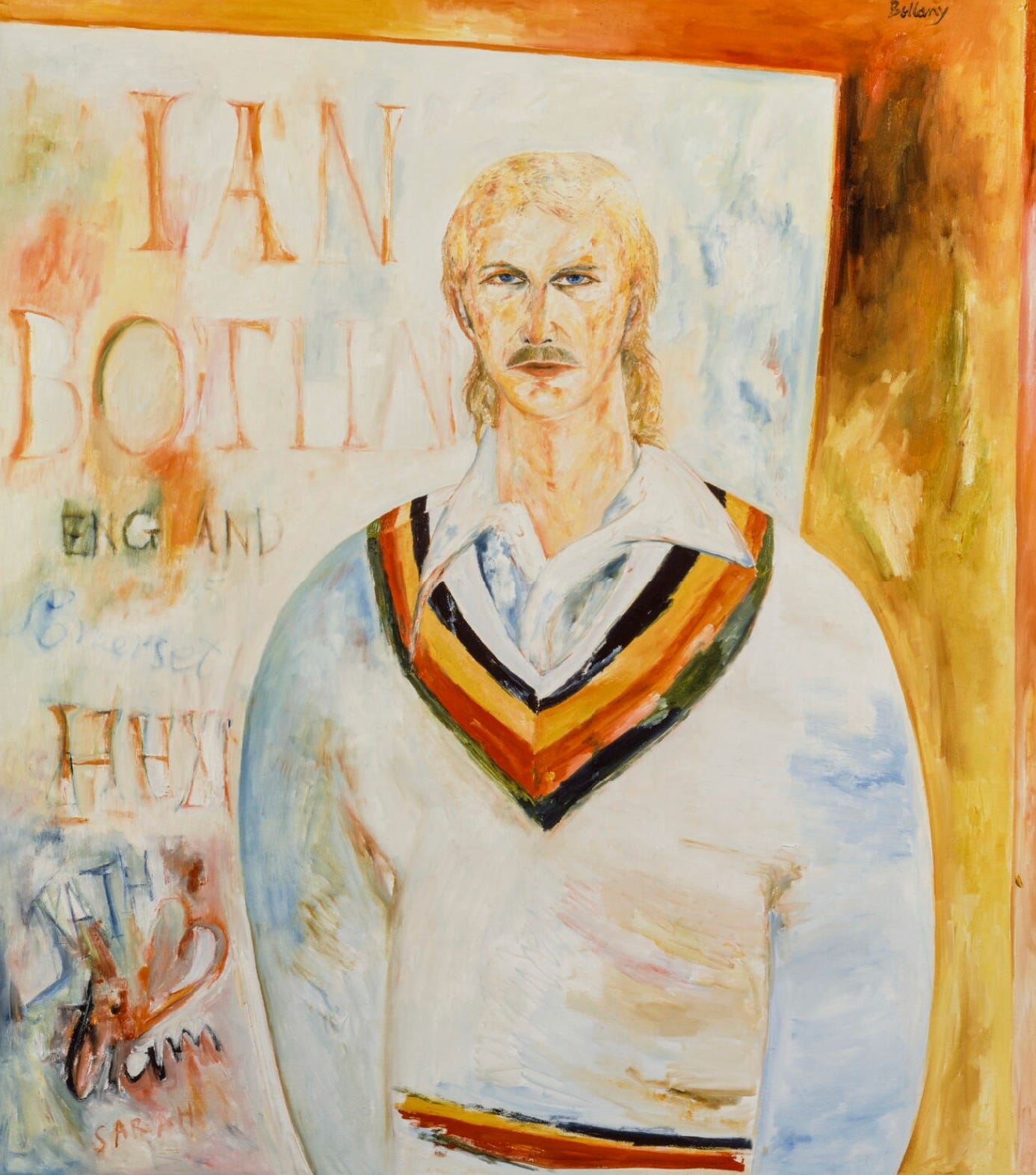

I never thought I would see an England cricketer greater than Ian Botham. Geoffrey Boycott says that he was the best that he played with. Mike Brearley’s reputation is yoked to Botham’s achievements. 1981 is a long time ago now and it may be impossible to conjour unless you were there to see it and to feel it, but it was the young Botham in excelsis, and his best came when he was young. The only day’s play I saw in the flesh was his downfall at Lord’s where he was out for a pair and resigned from the captaincy. It’s true that he walked off to silence from the members in the Pavilion, and you can only imagine how he felt in those eerie, oppressive moments.

Botham’s life transformed that summer, and arguably our national life changed with it. He became bigger than the game, appearing in TV adverts and on chat shows, and on the front page of the tabloids. And here was the shift that his fame affected, a cricketer being treated like a celebrity, up there with George Best and John McEnroe, followed around not because he was an athlete but because he was a story.

It was the end of the unwritten pact between writers and players. With Botham, nothing was off limits, not allegedly sleeping with a beauty queen in West Indies or suing Imran Khan for libel, not smoking a crafty spliff or big cigar, not his marriage or his children or anything else he did. The relationship between media and players changed and would never change back.

There was something colloquial about Botham, a man-in-the-street kind of ordinariness that was tied to his appeal. Away from the field he embodied something, the kind of bloke who took no nonsense, who stood up for things he believed in, walking out of a dinner when a comedian insulted the Queen, rucking with Ian Chappell in Australia, leaving Somerset in solidarity when they sacked Viv Richards and Joel Garner. When he attended a hospital appointment and by chance saw a child being treated for leukaemia, he began a series of epic charity walks that went on not just for a few years but for the rest of his life. He was somehow both Falstaffian and anti-establishment, a man of the people in the truest sense, and at a certain cost.

There’s a section in Peter Roebuck’s book It Never Rains where he observes Botham and Viv Richards in the Somerset dressing room looking completely at home in a way that Roebuck understands he will never be. Botham, to anyone’s certain knowledge, never seemed to worry about the game. He was so good, it would eventually take care of itself. Even when he could barely run any more, let alone bowl, he dragged England to a World Cup final almost single handed. For his last delivery in professional cricket, to Australia’s David Boon while playing for Durham, he opened his flies and ran up with, as he later put it, ‘the old man dangling in the wind.’

‘The New Botham’ tag was handed first to Derek Pringle even as Botham was still playing and it passed along the line to David Capel, Craig White, Phil DeFreitas, Chris Lewis and Dominic Cork, none of whom could bowl like Botham, let alone bat like him. And yet so long was the shadow, so deep the impression that Andrew Flintoff, four years old in 1981, was tagged with it too, and finally became the man to shake it off, somehow breaking free of history while maintaining the archetype.

Flintoff was in many ways friendlier than Botham, cuddlier certainly. He had a gentleness, a fragility even, that contrasted with the bluff, blustering figure that Botham became. By his final year in the commentary box, Beefy was ready to go and the public was ready to see the back of him. In a (luckily faint) echo of the famous stunt at Durham, his last stint on camera came while he was wearing shorts, demob happy. David Gower, who left at the same time, sharply felt the loss. Botham barely looked back. Now he is in the Lords, put there, it has been said, for his support of Brexit. In one way it is a fantastical end game, a journey impossible to envision that day he walked off at Lord’s after a pair.

It’s Geoffrey Boycott’s view that Botham failed as a captain because he was given the job too early, not just in years (he was 24) but in emotional maturity. I’m sure he’s right. Stokes, more so even than Andrew Flintoff, has worn his heart on his sleeve. He chose to expose the rawness of his breakdown in an Amazon documentary that came after the Mbargo trial and the death of his father. When England wobbled in the 2019 World Cup, he stood up and told the rest that he was scared of cocking it up too, but that was okay. He has not just shown his strength, but where it comes from, how it is constructed.

Maybe he has outdone Botham on the field. I thought Botham was the greatest England cricketer I had seen, not by the stats but by the unlikeliness of what he could achieve, yet Stokes has at the very least matched it and probably gone past. What they share is an ability to bring the game to a rare and heightened pitch. Stokes in the World Cup final at Lord’s was as mad and wild a spectacle as Botham at Headingley. I saw him bat live twice last Summer, once at Headingley when he made 80 while barely able to stand, and then at the Oval when he broke the highest ODI score against New Zealand. The most striking thing was the relationship between crowd and player. Stokes was the people made flesh and it was a rare communion.

In purely cricketing terms, I think Stokes is the better batsman, Botham the greater bowler, but that is almost irrelevant. Both will dominate their eras historically, but in very different ways. Stokes has an empathy as refined as his competitive desire. He has imposed a particular mindset on the English game in a way that Botham’s replacement Mike Brearley somehow did too, and he may be England’s most significant captain since Brearley, despite his record looking patchy and less impressive than his methods.

It turned out that Ben Stokes had been defending two men, a gay couple, when he got into the fight outside Mbargo. Maybe he didn’t do it in the right way, but he did it for the right reasons, and from its ashes he has risen. There’s no need for a ‘new Botham’ now – that has been Ben’s gift to Ian, and to the game.

A fair assessment, I think. Comparisons of innings are ridiculous as there are so many variables, but I think Stokes’ innings at Headingley was greater than Botham’s.

My main hobbyhorse in this area is Botham’s early bowling (circa ‘78-79). He was an exceptionally brilliant swing bowler before he put on weight and his back went. Superior to Jimmy Anderson, in fact, but only for 2-3 years, when Jimmy did it for 20 (though at his best post-35, which Botham, flies undone and all, certainly wasn’t).

You're right that his batting outweighs his bowling but my best "live" viewing of him was the 6-36 off 21 at Trent Bridge in 2015. You could almost feel the ball hooping in the dark, muggy atmosphere, over after over. Of course, it's overshadowed by Broad the day before...