Reputations: Viv and Brian

Our series continues by looking at where Lara ranks alongside the West Indies' greatest

‘I saw Viv Richards in his prime/Another time, another time’

I’m paraphrasing the great Pinter of course, but I did encounter immortality Richards-style on several occasions. The first was at the Oval in 1976, a Friday the 13th as it happens, and as inauspicious a date as could be for England’s bowlers, when Viv, undefeated on 200 overnight, walked out across the sun-scorched ground that morning and blew the scales from my childhood eyes. He made 291.

Who was this man? What was this game that he alone seemed to be playing?

The second was three years later at Lord’s, the World Cup Final. In he came at number three. Everyone knew who he was by then of course. He made his gunslinger’s entrance and scored 138 not out, hitting the last ball of the West Indies innings into the crowd by the Tavern. From an allocation of 60 overs, West Indies compiled 286, a score considered insurmountable back then, albeit one exceeded by Sunrisers Hyderabad in twenty overs the other day. Another time, you see.

A year or so later, it was Lord’s again, when he scored, from memory, 118 in a Benson and Hedges Cup Final for Somerset. In fact, the only time I ever watched Viv fail was in the next World Cup Final, 1983 against India and again at Lord’s, when he got to 33 from 28 deliveries, and we settled back to watch the slaughter of India’s popgun attack.

If you wanted to pin the emergence of cricket as it is today to a single point in time, what happened next is as good a moment as any. From the military medium of Madan Lal, Viv aimed one of those rock-back pull shots that he used to dismiss the unworthy from his presence and instead hit it almost straight up, Kapil Dev holding on to the swirling orb as it fell over his shoulder.

Viv Richards’ aura by then was so powerful, his myth so strong, the sense that he would define any game that he played in so entrenched, that everything around him came unmoored. India had only scored 183, but when Viv was out, West Indies folded and were dismissed for 140. Impossibly, they – he – had been beaten. It was like watching Ali knock out George Foreman in Zaire, the end somehow unlikely and inevitable and beautiful all at the same time. That day, the world’s face began its slow-motion turn towards India.

What was it about Viv Richards that made him quite so totemic?

I had one more encounter with him. This one came before the 2012 Olympic Games, when he visited the campus at Guildford University as part of Antigua’s promotional delegation. “Would you like to go and interview Viv Richards?” I was asked.

Well, as it’s only up the road, I could probably see my way clear…

On the way there, I kept thinking maybe I should tell him about the first three times I saw him bat: 291, then 138 not out, then 118 in the B&H. “So you see, Viv,” I would say, with an amusing flourish, “you were getting worse every time.”

Yeah, okay. “Do not,” I thought to myself as I got out of the car, “under any circumstances say that to Viv Richards…” Nonetheless, half an hour later, there I was sitting in front of him in a refectory at Guildford University with those very words somehow edging out of my mouth.

“So you see, Viv…”

Thankfully he laughed, and we talked for a bit about those innings, and how much his life had changed after the first of them on that wild tour of 1976, when he was 24 years old and practically unknown.

Then he said something, a single line, that I’ve always remembered and that seemed to unlock the truth about his cricket.

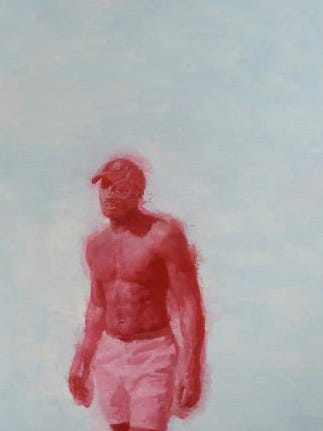

“With the bat,” he said, “I was a soldier.”

This was how he saw himself, how he saw the game. He may not have framed it in quite the way I’m about to, but he seemed to be talking about the existential nature of batting, the thread that it hangs by. It wasn’t in his character to be accepting of fate, because fate had usually worked out badly for his people. Instead, he brought weapons, he wore armour, he engaged in combat, he fought and he won and he lost. He was a soldier, a warrior king from a small island where his father worked in a prison that overlooked the cricket ground.

Gideon Haigh once wrote of Don Bradman that Australia had a ‘deferential incuriosity’ about The Don beyond his statistics. There was something about him that could not be touched or examined. Richards was not quite the same, but such was his hold of the imagination of the generation of cricketers that played against him and the next that grew up watching him that there was no alternative view, just the universal idea that he was the greatest batsman of the modern age, the Master Blaster, King Viv.

And Richards’ domination was not based on the stats. There was no empirical case for his superiority in the way that there was for Bradman’s. Bradman’s batting average was forty per cent better than anyone else’s. Richards’ stayed above 50 thanks to his final Test innings at the Oval in 1991. Make no mistake, he has a superb statistical record, but it was more about the aura, the destruction he wrought, the hold he had on the collective mind.

And then there was his meaning to West Indies, which, as mentioned in the Brian Lara piece elsewhere, was not a country in the way that the other Test nations were, but a construct that existed as a cricket team and a university and not much else. While Richards played, it was a single whole in which everyone believed. Since then, it has become fractured and waylaid by many different factors. The Fire in Babylon days were soon just memories.

What drove Viv Richards, it seemed, was this cocktail of macho pride in himself and in his sense of self, pride in his Blackness, his history, his island, his family, in all that he was and in the fact that he was self-made, that he alone had created this notion of what batting should be and then embodied it.

It has stayed that way despite the career of the one player I have watched who I would say was superior to him, perhaps even superior to Bradman, Brian Lara.

That may seem an absurd thing to claim, because Lara’s figures, like Richards’ figures, do not separate him from the rest. And yet at his peak, it was simply impossible to imagine that anyone could have been better.

Richards though remains a godlike figure, the symbol of a great cricketing empire. He still strikes awe in hearts wherever he appears. Lara is quite different, a more ambiguous presence.

I met him once, too. And just as encountering Viv was quite Viv-like in that he was the centre of attention and he knew it and satisfied everyone’s expectations with an easy, smoky charm, meeting Brian Lara was far more equivocal.

It was at a launch for one of his Brian Lara Cricket videogames at a tiny but packed bar in London. Most of the people there weren’t particularly interested in cricket, but in the gaming aspect of things. Lara, it transpired, had a whole other life as an avatar in that world, where his star had ascended in 1994, just as it had in real-time.

This must have been about the last of the series of games in which he was involved, in early 2007. Lara arrived dressed immaculately but looking harassed by all the attention. He had many interviews to do and was led blankly from one to the other. By the time he reached me, he had a glazed expression on his face (insert your own joke here). We were squatting on the edge of a shelf by a wall, which was slightly uncomfortable. It was obvious that I didn’t know anything about videogames, too, so I asked him about the milestone he was approaching, that of 12,000 Test match runs, a peak no-one had yet reached. He spoke quite keenly about getting there, and about his plans for the upcoming West Indies matches, as he had recently been made captain again for the umpteenth time.

I went off quite happily to write the story up. Just as it came out, he announced that he was retiring. It seemed a quintessential and quixotic Lara move, related more to events off the field than on it. He left the game as the highest run scorer in Tests, and with more than 10,000 ODI runs, plus those unapproachable, monolithic innings: the 277, the 375, the 400, the 501, and the others that were even greater demonstrations of his genius: the run against Australia in 1999, perhaps the final shiver of the West Indies dynasty, when he made 213 in Kingston, 153 not out in Bridgetown and 100 in St John’s. On many occasions he had destroyed the greatest bowlers of the age, apparently at will, and sometimes for days on end.

He did all of it not in a winning team but a fading and disjointed one. Part of Richards’ genius was that he had held this intangible thing together. Part of Lara’s was that he was untouchably great while it all fell apart, sometimes because of him.

What would have happened to Viv Richards had he been given, after that burning summer of 1976, a multi-million dollar house on his island’s prime chunk of real estate, as Lara was when he passed Garfield Sobers’ record Test score? They were both, coincidentally, 24 at the time those things happened to them. What would have happened had Lara existed in the 1970s, and been a part of that mighty generation? What would have become of Viv had there been videogames and the more prurient kind of fame that came in the 1990s and beyond?

Both knew one thing that most of us will never know: what it is like to carry the weight of expectation. They had a responsibility not just to their families and their countries and their islands and the West Indies, but to the glancingly rare talent that they had inside of them. Each fulfilled it in their own era and in their own way, and in the end, that’s all anyone can do.

I hope that history is as kind to Brian Lara as he deserves. No-one, not even the great Viv, batted quite like he did.

Somewhat late to this, Jon, but no less enjoyable for that.

A couple of thoughts: I think it’s a recognised phenomenon that the more you tell yourself not to say something the more likely you are to say it. I’ve certainly done that.

I saw Richards live (not 1976, but the 1979 WC final and the Gillette the same season), and I think Lara was better. The best batsman I’ve ever seen, and I tend to feel he doesn’t quite get his due. There’s the elegance, and the control, but also the sheer impregnability. I’ve sometimes felt watching Steve Smith or Joe Root that it’s unimaginable that they would ever get out, but nobody quite had that air like Lara. The winter after the 375 I was on Atherton’s tour in Australia and met a Yorkshireman who’d been in Antigua. He said that when Lara had about 20 he felt sure he was going to break the record. Sure enough, he did.

Having “seen Viv” is one of the great claims of our cricket-loving generation. I think that the game you mention from memory is the Gillette Cup Final against Northants, a few months after the ’79 WC Final – he scored 117, I was there too, heartbreaking but spectacular and never forgotten.

On the way home from playing yesterday I drove past Wellingborough School, a Northants outpost in the 70’s and 80’s, and thought, as ever, about the time, in a Sunday league game, that Viv hit the ball out of the ground, over the road and deep into the nearby Comprehensive. It’s a well told tale, maybe even exaggerated - I’ve even heard Graeme Swann mention it although, if I’m correct in dating it as 1978, it happened a year before he was born. Maybe he did it again?

And Lords 1983, what a day!