In August 2022, I wrote something for Cricbuzz about the Hundred, and how it only makes sense if you view it through the lens of money and what happened to the ECB with T20. As the great sell-off it predicted is apparently about to begin, and the original piece is behind a paywall, I thought we’d stick it up here as a bonus post. Just call me Nostradamus…

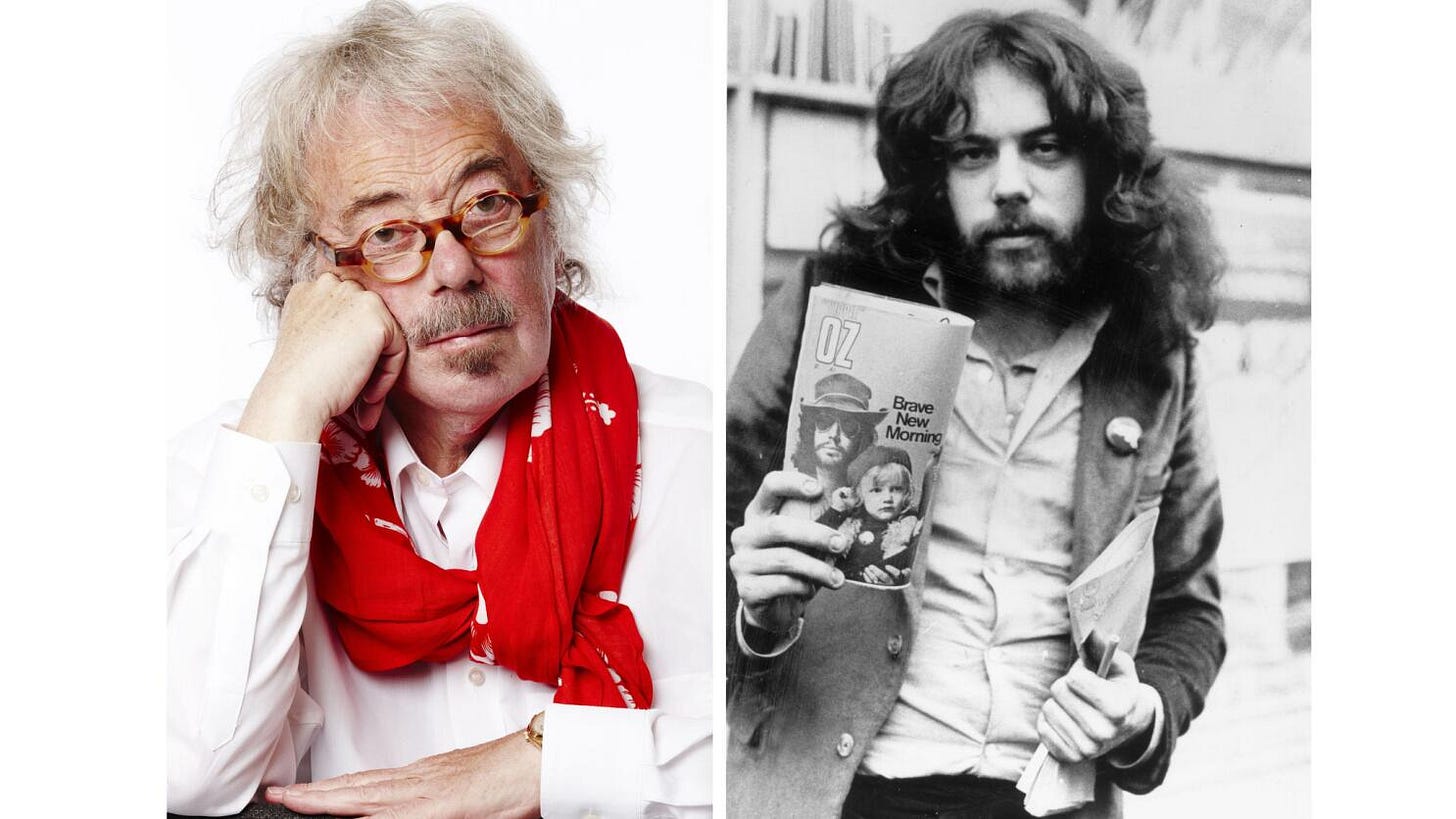

‘IF I have one ability,’ the entrepreneur Felix Dennis said, ‘it’s that I see what people want five minutes before they do.’

The first thing that Felix Dennis saw, way back in the 1970s, was a poster of Bruce Lee that folded to the size of a magazine so that it fitted on the shelves of local newsagents. It made him £60,000. He went on to publish magazines about the first home computers and desktop gadgets and became incredibly rich, and, despite an addiction to crack cocaine and sex workers that cost him, he reckoned, £100m, ended up with a mansion called Dorsington, where he commissioned a garden of life-sized bronzes of forty ‘heroes and villains’ including Einstein, Churchill and Stephen Hawking, and where he planted a forest of more than one million trees. In his final years he became a poet and organized readings where he gave the audience free wine from his cellar. All of this happened because Felix Dennis could sometimes see what people wanted five minutes before they did.

He also wrote a book called How To Get Rich, which I read because I quite fancied being rich, especially if all I had to do was read Felix Dennis’ book. It would be nice to plant forests and go on boozy book tours, I thought. But you may be surprised to learn that it turned out getting rich wasn’t easy. In fact, the opposite. Getting rich took demented levels of work and risk. The people that got rich ‘were utterly determined to, no matter what the cost.’ They never gave up, even when they were rich, because there was always someone richer, someone like J Paul Getty Jr, a noted cricket fan incidentally, who once said: ‘if you can actually count your money, then you’re not really a rich man.’

There was one other key piece of advice in Felix’s book. Ownership is everything. Ownership is ultimately what makes you rich. This is the thing that you really need to remember.

IN 2001, Stuart Robertson had an idea. It was an idea worth billions, literally. It was something he thought people would want five minutes before they knew they would want it. Stuart was a marketing manager at the ECB, and his idea was professional Twenty20 cricket. The chairs of the eighteen county teams that competed in English domestic tournaments voted it through, and the T20 Cup began in the summer of 2003. The players had no real clue about what they were doing or playing and at first found it a bit of a joke, but the crowd response was immediate and very different. They knew they wanted it, a cricket match that could fit into an evening and where the proposition was very simple: score as many runs as you can from the 120 deliveries available to you. Even as a novice, you don’t need to know much more than that to understand it. Anyone could sit there with a beer in their hand and watch it unfold.

But, and it’s a big but, the ECB broke another of Felix Dennis’ rules, the major one actually: ownership is what makes you rich. If you want to find a starting point for the Hundred and the knots that cricket in England is tying itself into, then that moment in 2003 is as good a one as any.

University students beginning their degrees in the UK this week [note: August 2022] were born in 2004, the first intake to have existed for their entire lives in a world of T20 cricket. They are too young to recall a time before the IPL. They have probably never heard of Lalit Modi, billionaire princeling of the OG T20 franchise event. But what Lalit Modi did with T20 cricket was kind of like what Felix Dennis had done with his Bruce Lee poster. The genius of the idea was not the poster itself. Anyone could have come up with it: in fact, other people did. The genius of Felix’s Bruce Lee poster was in its execution, in folding it up and making it into a magazine that fitted into the newsagents’ racks. This was important because fans of Bruce Lee didn’t go into art shops or places like that, but they did go into the newsagents. It wasn’t about the originality of the idea but the originality of the execution.

Lalit Modi’s genius was of a similar type. He didn’t invent T20. He invented the perfect execution of T20. He looked at American sports for a model because he had lived and studied in America and he knew how American sports made all of its money. American sport made its money from the franchise system, so Lalit executed that in a way that worked in India. And it worked spectacularly well. In England, the BBC called Lalit ‘a maverick impresario’ and ‘cricket’s answer to Don King and Bernie Ecclestone.’ King and Ecclestone were of course both very rich and masters of retaining ownership by any means necessary. Lalit Modi retained ownership of the IPL for as long as he could, until the BCCI gained control. Each game in the IPL is today worth $13.4m, the second-most lucrative sports ‘product’ in the world.

The T20 Cup, now branded as the T20 Blast, is not worth $13.4m per game. Its competing teams are not franchises. Its original idea, the idea of professional T20 cricket, is old. All of the other T20 leagues copied the IPL model and now their seasons eat hungrily into the cricketing year. Players, the good T20 ones, are spoiled for choice, no longer yoked to national boards or states or counties. This is the power of competition. This is the market, and these are market forces at work. To draw an analogy that people born in 2004 may have to google, the ECB were a bit like the guys who invented the home video recorder, the VCR, only they came up with the Betamax version, while the IPL was the VHS format, the one that everyone adopted. And Sony, the company that really did invent Betamax video recorders, eventually gave up and began making VHS recorders too.

In 2016, the ECB proposed a new, city-based T20 competition to the counties, and the counties voted it through. In 2017 another of their marketing executives, Sanjay Patel, had the idea of a game that had innings of 100 deliveries instead of 120. His idea solved several problems. It shortened the format, which for potential terrestrial TV broadcasters in Britain was attractive – games of T20 that lasted for four hours, as they did in the IPL, were still too long and uncertain for evening schedules. It (arguably) simplified the game for the new audiences that the ECB wanted and needed to attract. And it offered the chance to harmonise the men’s and women’s competitions. All of these things became more important in the grim, post-Covid landscape into which the competition launched. But most of all, The Hundred obeyed Felix Dennis’ rule. It granted ownership. It put the ECB back in the game, offered them a second chance to get rich after that one in 2003 had slipped away.

HERE’S another line or two from How To Get Rich: ‘Fear nothing. Another easy-to-say and impossible piece of advice. Tough luck, chum. Life’s a bitch and then you die. Get used to it. It isn’t going to change anytime soon… You cannot banish fear, but you can face it down, stomp on it, crush it, bury it, padlock it into the deepest recesses of your heart and soul and leave it there to rot.’

To get rich, you must pursue your goal dementedly, because the people that got rich, remember, ‘were utterly determined to, no matter what the cost.’ The ECB have bet the house the Hundred. They have sold August. They have sold it until 2028 to their broadcast partners, and now they have to sell the competition to the fans, market it, make it feel irresistible, because the level of investment – financial, emotional, structural – is terrifying. The ECB has gone all-in. It has faced the fear and done it anyway. And it has done it with myriad other challenges and problems bearing down, applying pressure, making the decision ever more vital. Ownership of the Hundred really is everything.

Viewed through this lens, the lens of getting rich, everything about The Hundred makes sense. Everything about The Hundred fits the get rich paradigm. The ECB has a new Chairman [note: as of August 2022]. His name is Richard Thompson, and in his previous post at Surrey, he opposed The Hundred, and was the only county Chair to vote against it. But he is a brilliant man, really very clever and a giant force at Surrey, which he has turned into a behemoth. He knows that the ECB and anyone else can have all of the reviews and consultations they want, can find a zillion ways to placate and pay off the counties and the existing fans of long form cricket, can address the moral dimension of The Hundred and its effect, but he cannot stop the future. When Richard Thompson gave his first interview to Mike Atherton in The Times, he talked about the value of ownership. He talked about how to get rich, even though he didn’t say it in that way.

‘You have to realise value,’ he said. ‘There is a lot of private equity out there… There is no question that cricket will attract private equity but what it can’t afford to do is be opportunistic. It needs to be strategic. Is two years too soon? Do you wait for it to develop further and increase its value? It shouldn’t be a kneejerk reaction. It [The Hundred] is clearly attracting interest but we need to do it in the right way. It’s a nice problem to have if we are creating value, which I think we are.’

Through our lens, the lens of getting rich, this means only one thing. There is a lot of private equity out there and the ECB cannot build another Betamax. It must obey the rules, the rules of getting rich. It must retain ownership, and make the franchises available for sale. Having created The Manchester Originals, The Southern Brave, The London Spirit, The Oval Invincibles, the Welsh Fire, the Northern Supercharges, the Trent Rockets and the Birmingham Phoenix, having conjured them from the thin air of imagination, it will sell them to the highest bidders. It will take its poster of Bruce Lee and fold it up into a size that will fit in the racks, where the right people will find it and then buy it. It will not be original but it will, with Richard Thompson, be properly executed. Sometime in the future, not yet but soon, the ECB might once again be rich.